Systemic Performance, Openness, and the Politics of Resentment

The Illusive Idea of Productivity

Systemic Performance, Openness, and the Politics of Resentment

The Illusive Idea of Productivity

Pasquale Lucio Scandizzo

Productivity is the most used and the most difficult concept in economics. At the firm level, it is defined as the ratio of output to inputs: how much a firm, industry, or economy produces using a particular combination of labor, capital, and other inputs. Because it must be expressed in monetary terms, however, its measure becomes problematic when firms with market power can influence one or more of the underlying prices. But when we move beyond the firm level and begin making cross-country or intertemporal comparisons, the concept becomes even more prohibitively difficult to define and use as a basis for meaningful measurements.

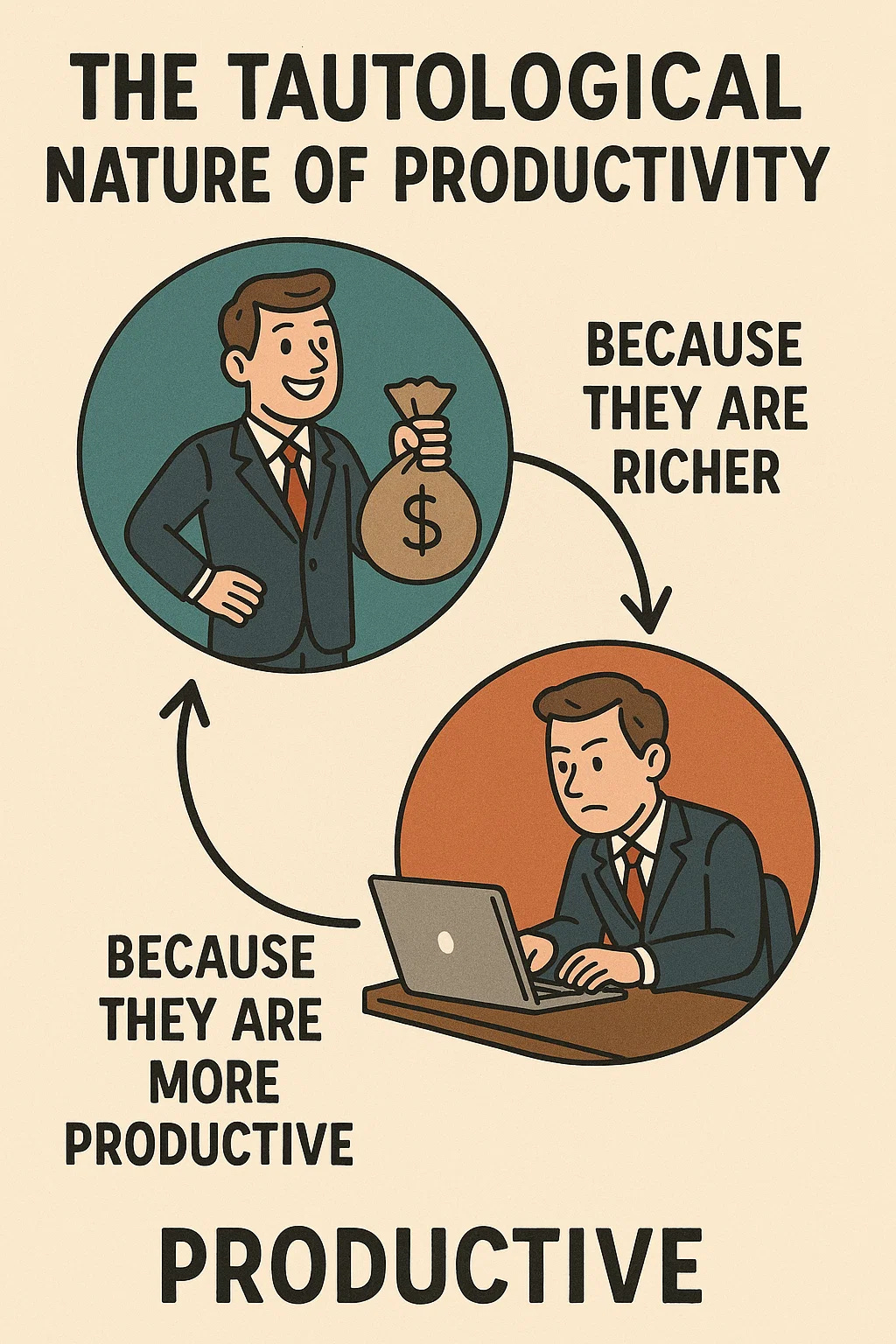

The problem is that, despite its widespread use, productivity estimates run into an inevitable tautological trap by overlooking the issue that monetary values are unreliable for combining diverse goods and services. As Arthur Lewis persuasively argued more than 70 years ago, this tautology breeds the conclusion that those who reap the highest benefits from production are more productive than others, regardless of their market power, political influence or the favor of the circumstances. This is the simple result of the fact that what qualifies as “more productive” usually isn’t a measure of inherent efficiency, but of the relative value of goods and services according to a contingent and essentially arbitrary order of prices and preferences. A sector may appear more productive because the prices for the goods it produces are high, while these very prices are evidence of institutional contexts, configurations of the market order, and regimes of commerce. Standard measures of productivity, even in their most sophisticated econometric forms, often reflect price and wages differences rather than effort or output, especially in increasingly service-driven economies. Moreover, they typically don’t consider critical components of the welfare-improving content of what is produced, especially if this involves public goods or other positive or negative external effects. According to these measures, for example, a firm that provides high-margin luxury goods may be considered more productive than a firm that provides health or education services and adds more value to social welfare. Similar problems arise when we consider productivity changes over time, because any productivity index still requires a baseline and because the value weights to aggregate the different outputs may themselves change.

The measurement problem is thus a valuation and pricing problem and is one and the same of the much-debated question of the appropriate use of GDP statistics to measure aggregate contribution to wellbeing. The point is that these statistics are based on the concept of value added, which depends in turn on a mixture of prices and wages (as well as exchange rates in international comparisons). They thus critically depend on the overall economic and institutional context. A free trading regime gives rise to one set of relative prices and a protectionist regime to another. What is productive in one context may be less productive in the other. Productivity is not then merely a technically defined feature but an institutionally and socially embedded entity.

Productivity as a Systemic Property

Beyond measurement, the real issue at hand is the way the concept of productivity is typically framed. Traditional perspectives view it as resulting from advanced technology, increased effort, or improved organization. This positions productivity as a local property that must be won by competition. In turn this gives rise to a concept of “competitive advantage” based on the idea that productivity differences explain differences in economic performances at microeconomic level, and these are the final determinants of macroeconomic performance and ultimately of the wealth of nations.

However, productivity is not an exclusive characteristic of individual performers in a competitive game. It is rather a systemic feature, where the system extends beyond national borders and includes other national and international features of the global interconnected economy. It is the result of interactions among firms, industries, and nations in larger webs of commerce, finance, and knowledge spillovers. The productivity of a firm is not a function solely of internal process, but also the strength of its regular supply providers, logistics for hauling goods, active markets, and diffused technologies. The productivity of a nation is not a function only of home endowment and policies, but foreign value-chain membership, openness to new ideas, and membership in the global set of international institutions. Productivity in this sense is relational, cumulative, and emergent. It cannot be understood, nor increased, within bounded firm or national borders or by using a narrow concept of zero-sum competitive performance. Globalization has greatly increased the system properties of productivity, by enhancing its cross-country spillover effects through a system of international value chains that cut across national boundaries in a highly interdependent global network. As a result, productivity increases in one country tend to have positive powerful effects in other countries and benefits from technological change, better organization and competition are more widely distributed and encourage progress all over the world.

Openness is thus an engine of growth that drives systemic productivity by enabling specialization, competition, and the flow of ideas across borders and thus enables innovation and greater efficiency everywhere. However, in an increasingly globalized economy, openness also produces more frequent and deeper change, which creates winners and losers. Formerly prospering industries, skills, and places can fall into hard times; societies may not only lose jobs but identity and stability. Theoretically, the welfare gains through openness are large enough that the beneficiaries can compensate the losers. Practically, the compensation is partial or politically unavailable. The adjustment mechanisms lag behind and the social and cultural costs from disruption cannot be easily paid in the form of monetary transfers.

This creates a paradox: openness breeds systemic productivity, but its distributive consequences are unpredictable and often unpleasant to the extent that they invite the reversal of the very policies that have allowed openness to be established and open nations to prosper. Both across and within countries, winners from openness are concentrated and visible; the losers are often diffuse and abstract. As the dislocation from change accumulates, the coalitions of the excluded may mobilize to counter or reverse openness even if aggregate inefficiency follows.

J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy poignantly conveyed the anger generated by openness economic changes in the traditional fabric of American society; an anger now condensed in more general and somewhat chaotic form by the MAGA narrative. This anger depends on forced changes in living standards, lifestyles and social identities, which frame openness as a tool of betrayal rather than as a source of progress. This narrative is convincing because it identifies real moments of dislocation even if it mistakenly identifies causes and provides harmful solutions. These solutions include a measure of renewed American isolationism, combined with tariffs, quotas and reshoring. They appear both politically compelling and economically harmful. Disintegrating supply chains, inflating the prices of inputs, and stifling knowledge flows, protectionism erodes systemic productivity. It doesn't restore lost equilibria; it solidifies inefficiency and stagnation.

The international economic order is thus living a difficult moment, which is compounded by the growth of winner-take-all dynamics, particularly in the digital economy. Network externality, economies of scale, and data accumulation, as well as growing market power allow a small number of multinational corporations to capture excessive shares of the gains in productivity. This widens inequalities: the star firms, locations, and workers prosper while the majority stagnate or shrink. Rather than offsetting unfairness, openness in such a scenario broadens it, creating new patterns of exclusion that undercut social cohesion and legitimacy.

This imbalance begets bivalent coalitions. The dispossessed by openness mobilize to overthrow the system and react against perceived outside winners, like China and other foreign scapegoats. At the same time successful large corporations secretly benefit by disruption and institutional deterioration and from increasing their gains from monopolistic rent under the growing protectionism.

Nietzsche’s Ressentiment and the Modern Mood

A famous philosopher of the 19th century, Friederich Nietzsche, anticipated the psychological status and the cultural and political dynamics of modern society middle class through the concept of ressentiment. Ressentiment is a form of resentment which is not fleeting grumbling, but a long-smoldering state of resentment and envy rooted in perceived injustice and powerlessness. It flips values by seeking scapegoats and constructing narratives of betrayal. Modern globalization has made ressentiment a pervasive aspect of society, based on a sense of betrayal, envy and exclusion. Even if aggregate welfare increases, the individuals who feel excluded attribute their perceived bad fortune to the fact that other individuals: foreign competitors, elites, immigrants, or multinational corporations, have wronged them by prospering at their cost. This begets populism, conspiracy explanations, and resentment of cosmopolitan values.

Above all, ressentiment converges on the structural predominance of winner-take-all corporations. Populist grudges undercut institutions while monopolistic corporations flourish in the vacuum the destruction of trust and regulation has created. This further feeds on the false idea that productivity increases abroad, damage performance and wellbeing at home. The end result is a toxic cycle in which systemic resentment ultimately endangers systemic productivity.

Conclusions

Productivity is an elusive notion, difficult to quantify, compare, and conceptualize. It is always conditional upon an existing system of possibly divergent orders of preferences across individuals, social groups and nations. It is also contingent on regimes of protection and opening and upon institutions and prices. More than anything, however, it is not an independent attribute but a systemic feature of interdependence. Openness enhances systemic productivity, but may also encourage dislocation, resentment, and inequalities.

Resentment: ressentiment in Nietzschean vocabulary, becomes the signature mood of society, driving rearguard backlash and centripetal monopolistic concentration. The present disruption of the world economic order can be interpreted as a warning and a major call to political action: unless tensions innate in openness are solved by new institutions and narratives, systemic wellbeing (and productivity) will fall victim to systemic resentment.